A well-known mathematical conundrum, referred to as “The Monty Hall Problem,” revolves around the probabilities faced by a game show contestant aiming to secure a car hidden behind one of three curtains.

It questions whether changing their initial choice, once one curtain is revealed, would enhance or diminish their prospects of winning the grand prize.

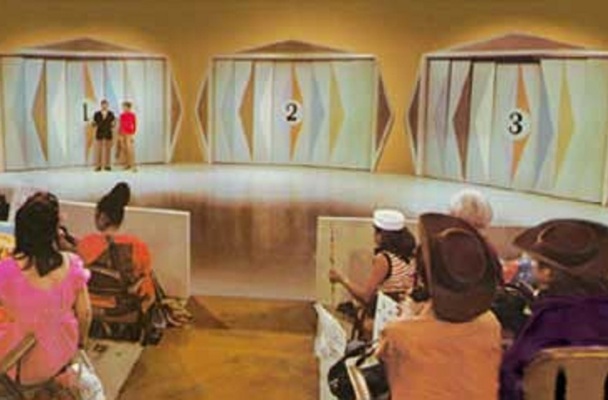

Essentially, this enigma presents a scenario where there are two goats and a car behind three numbered curtains.

The contestant selects Curtain 1, and if the host subsequently exposes a goat behind Curtain 3, should the contestant make the smarter move by switching to the curtain that hasn’t been revealed yet or sticking with their initial pick?

The correct course of action is to switch, as the problem posits that if their initial chances of winning were 1/3, gaining knowledge about one curtain not holding the coveted prize would increase these odds to 2/3.

It’s undoubtedly a perplexing concept.

Notably, one of the most famous instances of this problem in popular culture is a scene from the movie 21, where it’s employed to demonstrate the intelligence of the main character.

To further substantiate the argument in favor of switching for our hypothetical contestant, we need to introduce another key assumption.

It hinges on the notion that the host of this game show possesses complete knowledge of what lies behind each curtain and strategically selects which one to unveil.

Consequently, the act of opening one curtain instead of another is not a random occurrence but rather a deliberate choice guided by information known to the host but concealed from the contestant. Many individuals attempting to solve

The Monty Hall Problem tend to overlook this critical detail, leading to incorrect conclusions or a failure to grasp the rationale behind the correct solution.

This brings us to the relevance of this intriguing problem to our current discussion for this month.

The Monty Hall Problem derives its name from the original host of “Let’s Make a Deal” and serves as a quintessential example illustrating two essential points.

First, it highlights why “Let’s Make a Deal” differs significantly from many other classic shows, even though it presents itself as a lighthearted studio production not vastly distinct from “The Price is Right.”

Second, it underscores the broader issue of underestimating a show’s host or dismissing them as mere spectacle and comic relief.

However, there’s a crucial point to consider.

“Let’s Make a Deal” can present itself in any way it desires, but as demonstrated by The Monty Hall Problem and a close examination of the show, it turns out to be one of the most intellectually challenging conundrums in the realm of television game shows.

This isn’t to suggest that “Let’s Make a Deal” lacks entertainment value or harbors any malevolent intentions from its producers and the network.

But unlike the majority of other game shows that thrive on audience engagement and contestant self-doubt, “Let’s Make a Deal” proves to be a bit more demanding in terms of winning and exerts a manipulative influence on all involved.

The host plays a significant role in creating this impression.

Both the revived version of “Deal,” which airs in the hour preceding “The Price is Right” and is hosted by Wayne Brady, who has found his niche outside of 90’s comedy hours, and the original long-running program from the 1960s and 1970s on NBC, don’t come across as outright malevolent, but they don’t quite exude the uplifting aura one would expect from a game show that bestows extravagant prizes and substantial sums of money.

To begin, the studio audience dons flamboyant and often embarrassing outfits, which, rather than endearing the viewer to the participants, can be perceived as an inside joke that feels uncomfortable to watch and bewildering.

Moreover, the gameplay, in general, appears to oscillate between randomness and being agonizing for the viewer.

In contrast, “The Price is Right” effectively utilizes its studio audience in an organized manner – participants get chosen, engage in competitive bidding against three others for a chance to come on stage, partake in a familiar yet random game, and either seek assistance from the audience or succeed or fail in a structured fashion.

This structured approach enhances the viewing experience, whereas “Let’s Make a Deal” often comes off as chaotic, leaving everyone uncertain about what might happen next.

Although unpredictability can sometimes be a positive element, it frequently resembles a calamity occurring on a studio back lot.

“Let’s Make a Deal” was recognized for featuring a variety of deal categories, all of which revolved around the core concept of striking a relatively straightforward bargain.

While this unpredictability could be perplexing due to the element of surprise, it was also a source of entertainment on several levels.

The amusement stemmed from watching someone engage in a serious negotiation while dressed in bizarre attire, such as an adult-sized diaper, a chicken outfit, or as a ballerina, creating a comical juxtaposition between Halloween-like costumes and ordinary daily situations.

Also Read: Game Night: Notte Gioco

Furthermore, the inherent confusion in the show was advantageous for viewers seeking pure entertainment rather than a structured narrative arc involving contestants.

The absence of a clear end goal beyond the immediate deal made it an ideal show for those multitasking at home or spending time with family, not necessitating their full attention.

This leads us to perhaps the most distinctive characteristic that sets “Let’s Make a Deal” apart from other game shows, both from the 1960s and beyond, and has fundamentally shaped its identity.

In this show, all contestants were essentially competing against themselves, with only a few exceptions involving multi-participant mini-deals.

While they interacted with the audience and the host during their decision-making process, there were no other contestants vying for victory if someone made an incorrect choice.

It was a simple binary outcome – you either won or lost, you received a goat or a car, or you left with a pencil eraser or a thousand dollars.

At no point in the episode did contestants have to face off against a panel of rivals to prove their worth.

It was just them, the host, a couple of models unveiling curtains, and their own inner doubts about the choices they made.

This brings us back to The Monty Hall Problem and its connection to the classic show and its participants.

Much like individuals attempting to solve the problem, every contestant on “Let’s Make a Deal” goes through approximately four stages of intense self-doubt regarding whether they made the right decision or squandered the opportunity for a dream getaway to an island or another prize.

It unveils the sadistic aspect of the game show circuit, where contestants can only blame themselves.

On other game shows, participants may indeed make costly errors that deprive them of the grand prize, but in those cases, it’s often subtle enough that they could have overlooked it, or they can attribute their failure to someone else’s abilities.

In “Let’s Make a Deal,” contestants find themselves repeatedly second-guessing decisions they were initially confident about, driven by human nature’s innate tendency to harbor unwarranted concerns.

The host plays a pivotal role in this equation, mirroring the extent of their influence on the problem’s dynamics.

Monty Hall (who continued to make guest appearances as recently as this year), along with Geoff Edwards, Bob Hilton, Billy Bush (let’s conveniently forget about that reboot), and the current host Wayne Brady, have all embodied the most crucial hosting position on any game show.

It’s not to diminish the importance of other hosts in any way; for instance, Alex Trebek secured his place in history simply by maintaining unwavering consistency while presenting questions and answers five nights a week.

However, in the case of “Let’s Make a Deal,” the host holds the responsibility of sowing the seeds of self-doubt that each contestant must experience to make the entertainment value truly worthwhile.

This role is perhaps most akin to what Howie Mandel and the banker were tasked with on “Deal or No Deal.”

Without strategically inserted prompts like “Are you sure?” or “Would you like to change your pick?” there would be no element of uncertainty, and it would devolve into people trading items in their bag for a few dollars.

The enjoyment in watching arises when there’s a genuine possibility that someone might walk away with livestock, all while the host knows that a brand-new convertible awaits behind Curtain Number 3.

It might seem like a somewhat cynical perspective to adopt when considering a show as popular and well-regarded as “Let’s Make a Deal,” which has maintained a presence in various forms for numerous years.

This perception is likely influenced by the fact that “Deal” possesses certain distinctive elements compared to the broader game show landscape, leading viewers to initially focus on its unique aspects.

The show’s tone can be somewhat surprising, and the multiple reboots it has undergone over the years raise eyebrows.

In many ways, it retains a 1960s-style essence due to its absence of a complex narrative and its subtle mockery of the audience.

Modern shows typically revolve around teamwork or draw inspiration from previous question or challenge-based concepts.

“Let’s Make a Deal” doesn’t quite fit into either category.

However, Wayne Brady has successfully brought it into the 21st century with his sharp wit, all while traversing through a studio audience armed with only a microphone and a wallet full of bills.

While individual elements of “Deal” can be compared to other game shows, it remains one of the few shows that stands on its own, possessing a distinct sensibility and focus unlike anything else, all while managing to inject some fun into the midst of it all.

Fun Facts:

- “Let’s Make a Deal” has been broadcast on every major network except for Fox, spanning various time periods and networks: NBC (1963–1968, 1990–1991, 2003), ABC (1968–1976), and CBS (2009-Present).

- In 1974, this show boasted the lengthiest waiting list for studio tickets compared to any other show on the air, with a wait time of 2-3 years after the initial request just to have the opportunity to join the 350-person audience.

- It’s estimated that “Let’s Make a Deal” has aired over 5,000 episodes. However, confirming this number is challenging because most of the original tapes were wiped by NBC during the initial network run due to the high cost of video production.

- The show has been filmed in three locations outside of California at some point in its history: Vancouver, Orlando, and Las Vegas. The Las Vegas location likely added an interesting twist to the variety of outfits contestants came up with for the show.

Also Read: Game Night: Double Dare/GUTS